Peter Trachtenberg

Winter 2025 | Prose

On Waste Remediation: excerpt from The Twilight of Bohemia: Westbeth and the Last Artists in New York (Black Sparrow, April 1)

Barton Beneš’s aunt Evelyn kept sending him letters. She wrote voluminously, compulsively, her productivity brought about, or at least given extra oomph, by diet pills. (In the late sixties there was a type called Eskatrol. It was brilliant nomenclature, a portmanteau of ‘escalator’ and ‘control’; the hiss of the first syllable was like one of those shoulder-mounted rocket launchers that can take out a tank.) At the height of the correspondence she sent the artist a fifty-page, typewritten, single-spaced, double- sided letter two or three times a week. He tells the story in Barton Beneš: No Secrets, a documentary by the filmmaker Joseph Lovett.

“One day she asked, ‘Are you gay?’” He rolls his eyes at the camera. “Oh Jesus! So, I said, ‘Yeah,’ and that started the whole thing.” Evidently under the common misapprehensions of the time, Evelyn took her nephew’s queerness as a license to unpack her own sex life from the trunk in which it was usually kept. “She would talk about outrageous things, you name it. If it was typed on pink, it was meant to be very personal . . . to be read only by me. These letters kept coming. I didn’t know what to do with them, they were taking over my whole life.”

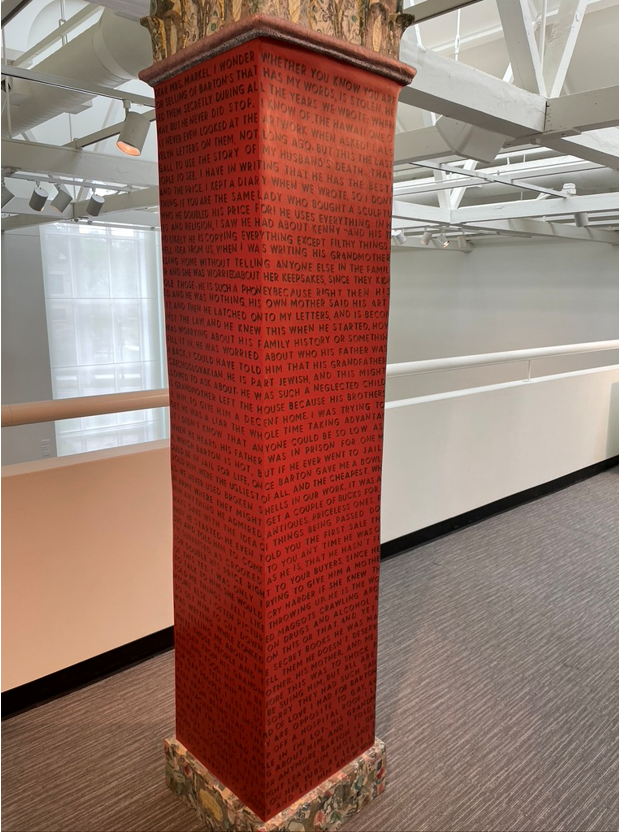

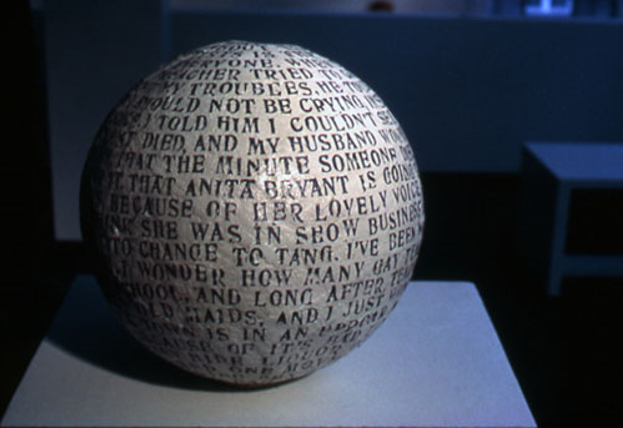

Somebody else would have sent them back stamped MOVED, ADDRESS UNKNOWN. Beneš used them. He copied portions of the letters onto oversized canvases. He wrapped their text around an architectural column; he hand-lettered excerpts on the insides of broken eggshells. He made six hundred books with them. When Aunt Evelyn wrote him about her flirtation with a rep from the company that made her typewriter ribbons (“That man from the typewriter company who I complained to about those dried-up ribbons said, ‘I’ll bet you can do lots of things.’ I don’t know what the man had in mind that he felt I could do. He is definitely interested in me personally, especially over the phone.”), he reproduced the words on giant spools of typewriter ribbon.

Barton Lidicé Beneš, Letters From My Aunt Evelyn, North Dakota Museum of Art

Barton Lidicé Beneš Letters from My Aunt Evelyn, Anita Bryant (1979)

Barton Lidicé Beneš, Letters from My Aunt Evelyn (1970s), Modernism Gallery

One sometimes reads that artists make work to exorcise the unwanted contents of their psyche. Beneš was exorcising the unwanted contents of his aunt’s, which she’d forced into his psyche via her barrage of letters. He was practicing a kind of artistic waste removal. Evelyn discharged plumes of grievance and self-praise, coquettishness, advice, scolding, spite—all the particulates produced by anybody’s brain on speed; Beneš suctioned them up and sealed them in different media and materials. She sent out more, he scrambled to contain them. He was like poor Mickey Mouse in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, frantically bailing out his master’s flooded workshop while the brooms he has called to life mindlessly go on flooding it. Except Aunt Evelyn was not a broom, and he hadn’t called her to life.

Seen in the aggregate, the pieces Beneš called Selected Parts of Letters from My Aunt Evelyn are droll, ingenious, whimsical, bitchy, but also exasperated, as if their creator were inwardly groaning, Will you shut up already! Eventually, Aunt Evelyn found out what her nephew was doing. For some unknowable reason, the hustler Beneš had hired as a birthday gift for his partner Howard wrote her and told her what use her nephew was making of her letters. “She freaked out and she stopped writing to me,” Beneš tells the filmmaker. Then, after a thoughtful pause: “And it was time, anyhow. I always find when I do something a long time and everyone likes it, it’s time to move on.”

Beneš moved into Westbeth in 1970, around the same time he gave up traditional painting. He’d already had indications he wasn’t suited for it; his brother Warren has a student canvas on the back of which one of Beneš’s instructors at Parsons wrote, “Barton, please don’t try to become an artist in your future life.” Around the time he landed his Westbeth apartment, he traveled to West Africa, where he was struck so forcefully by the ceremonial masks and statues he saw in every marketplace that whatever he’d done or wanted to do as an artist up until then no longer made sense. “Everything that was around, they made art with,” he told Lovett, who was one of his best friends. “Whatever you threw away was picked up and turned into art. I never painted after Africa.”

For most of his career, dealers and curators had a hard time describing what it was that Beneš did. “He’s not making abstract paintings, he’s not making figurative paintings, he’s not making minimalist sculpture,” says one commentator in Lovett’s film. “He really seems to have evolved his own particular, individualistic, odd way of making art.”

One might best describe Beneš as a repurposer; it places him in the lineage of the African artists whose work thrilled and humbled him. His materials included cowrie shells—a standard decorative element in West African statues and masks that he started using after returning to the US— money, human ashes, gallstones, pubic hair, scavenged bits of canvas and blobs of paint from the studios of more famous artists, and his own HIV-positive blood, assorted vessels of which were nearly impounded by Swedish authorities from the gallery where they were being shown. It’s fitting that a repurposer like Beneš would find a home in an apartment complex that was itself repurposed from offices and laboratories. He told his brother, “When you take insignificant items and you put them together, it then tells a story and becomes art.”

Peter Trachtenberg is the author of the memoir 7 Tattoos, The Book of Calamities: Five Questions About Suffering and Its Meaning, and Another Insane Devotion, a 2012 New York Times Editors’ Choice. His honors include Whiting and Guggenheim Fellowships and the Nelson Algren Award for Short Fiction. He is a professor emeritus in the Writing Program of the University of Pittsburgh and former faculty at the Bennington Writing Seminars. He lives in the Hudson Valley of New York. His Substack “Not Dark Yet” can be found at petertrachtenberg.substack.com.